Butterflies and moths

Butterflies and moths

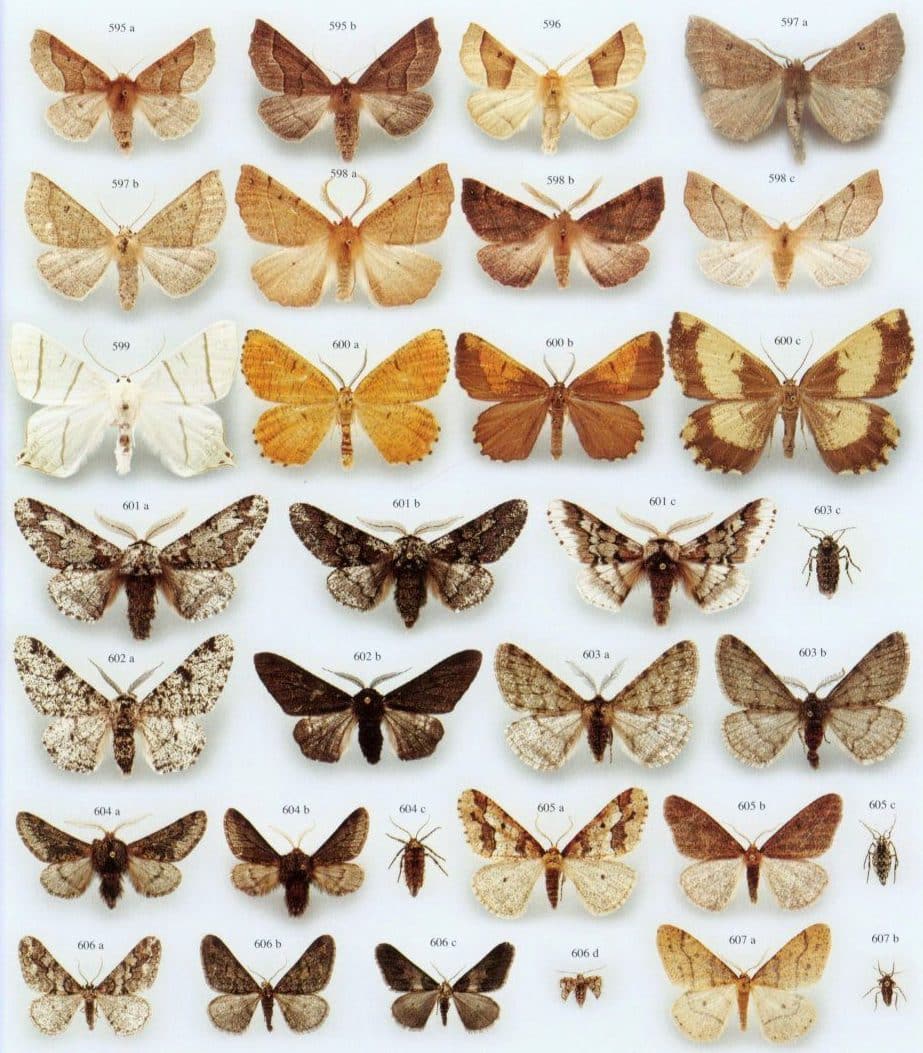

If we know and collect mainly butterflies or day butterflies, about 20,000 species currently known to science, the moths would be at least 200,000, or ten times more numerous.

Even from a distance, it is easy to recognize butterflies by the shape of their wings and their color, including Morphos with bright blue wings.

Scientists speak of diurnal butterflies or Rhopalocera and nocturnal butterflies or Heterocera. The first ones, which interest the collectors as well as the general public, because of their colored wings, are however and by far the least numerous. Better known, even by entomologists (scientists who study insects, including butterflies, but not only…), the Rhopalocera or diurnal butterflies, would be represented by about twenty thousand (20 000) species known to Science and certainly a few thousand species would still be discovered in the tropical jungles and other forests of the planet.

The bright red color of this African rhopaloceran, serves to attract females for reproduction. In the vast majority of butterflies, the wings of males are brightly colored while those of females of the same species are generally quite dull.

The moths are ten to twenty times more numerous than the day ones.

Science knows about ten times more species of Heterocerans or moths, between one hundred and fifty and two hundred thousand (150,000 and 200,000) and certainly several tens of thousands of species are still to be discovered. As a comparison, the mammals of which we are a part are represented by only about 4600 listed species.

Easily recognizable by the shape of their wings, but especially by their dull, gray or brownish colors and even more so by their "feathery" antennae, Heterocerans or moths, are much less sought after by collectors who prefer the brightly colored Rhopalocerans.

The Rhopaloceras, so called because their antennae are terminated in the shape of a club (from the Greek Rhopalon), stand at rest with their wings generally folded or joined upwards, or else, but less frequently totally spread out, letting their magnificent colors appear. The Heterocerans or moths have characteristic antennae, much larger, called feathery or comb-shaped. At rest, their wings are generally quite dull (gray or brownish) and are folded in the form of a roof on their back.

A very close-up under the microscope of a butterfly wing, showing the scales that cover it, like the tiles of a roof. Note that these scales have neither the same color, nor the same shape.

Lepidoptera from lepidos (scale in Greek),

means wings covered with scales.

These two “groups” of butterflies, however, have a common characteristic, which makes them belong to the order of Lepidoptera, scientific name of butterflies in general, ie to have scales (often tiny) on their wings. From the Greek lepis (scale) and pteros which means wing.

These scales are stacked on the wings like tiles on a roof. When we catch a butterfly and touch its wings, the powder that remains on our fingers is in fact a pile of these tiny scales. This will not prevent the butterfly from flying, provided that the transparent membrane on which the scales are stacked is not torn.

It is the pigmentation of the scales that gives the different species of butterflies their colors so different from each other. These colorations which can compete with the most accomplished or sublime paintings, have in fact two main functions: to allow the identification of congeners and thus the mating within the same species, but also to deceive predators by imitating a leaf or a flower, or even to frighten them by certain patterns such as the ocelli which imitate eyes

Splendid Rhopaloceran (diurnal butterfly) easily recognizable by its brilliantly colored wings and its club-shaped antennae (Rhopalon in Greek). On the underside of its head, its proboscis allows it to pump nectar from flowers, which it feeds on.

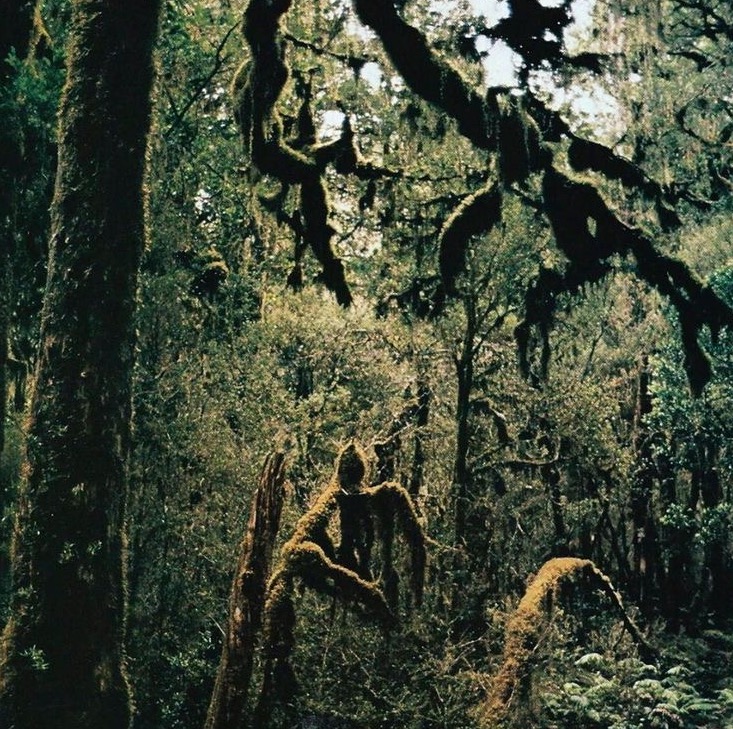

The tropical jungles of the world are the biotopes that host the largest numbers of insects in general and butterflies in particular.

In metropolitan France, there are only about 250 species of butterflies (Rhopalocera), some of which have unfortunately disappeared, while there are about 5,000 species of moths (Heterocera), nearly twenty times more. As a comparison, there would be in the only “small” department of French Guyana, at least one hundred times more species of lepidopterans (diurnal and nocturnal), than in metropolitan France. The entomologists of the National Museum of Natural History of Paris identify every year in the Guyanese forests dozens of new species of butterflies, especially nocturnal.

In metropolitan France, butterflies are on the verge of extinction.

Once quite abundant in mainland France, the machaons of the family Papilionidae are now in danger of extinction, and some species are even extinct. The rarefaction of their natural meadow habitats, but especially agricultural pesticides are the main causes of this dramatic decline.

In the large family Saturnidae (moths) butterflies are present throughout the world, including some species in France.

In all our regions of intensive agriculture (wheat, corn and other cereals or monocultures such as rapeseed), pesticides or, to be politically correct, agricultural “phytosanitary” products, destroy insects in general, first and foremost the caterpillars of many species of butterflies, beetles (beetles, ladybugs, chafer beetles, etc.), grasshoppers and when, after rains, these products end up in streams and rivers, they wipe out butterflies.

When these products end up in streams and rivers after rainfall, they destroy the larvae or adults of many insect families that spend a large part of their life cycle in water, such as dragonflies, mayflies, caddisflies and many dipterans that are dear to fly fishermen.

Those of us who are over sixty years old remember that in the spring and summer, before the eighties, we had to clean the windshields of our cars every hundred or two hundred kilometers where butterflies crashed, and if the road bordered a river hundreds of mayflies or caddisflies.

It is a long time that “thanks” (not returned) to pesticides, sorry, phytosanitary agricultural, this work of cleaning windshields is no longer necessary.

According to numerous European studies, the decrease of more than 70% of the wild birds in our regions, during the last thirty years, is essentially due to the fact that they no longer have insects to eat…

These two African rollers are fighting over a papilionid.

Only in a few regions of Brittany (the Armorican mountains), the Massif Central, the Jura, the Pyrenees or the Alps, in valleys too deep to grow and harvest cereals, are there still good populations of butterflies and other insects.

The most beautiful example is represented today in Provence, by the high valley of the Durance and the Bléone around Dignes-les-Bains, in the department of the Alpes de Haute-Provence. It is in this small valley, that the specialists of the National Museum of Natural History still count today approximately 135 different species of butterflies (Rhopaloceres), that is to say on a very reduced territory, more than half of the diurnal butterflies listed in all France.

So much so that a Butterfly Garden was created about fifteen years ago, in the commune of this small sub-prefecture, and is open to the public. In a very beautiful and wild natural setting, depending on the season, parents and children can discover dozens and dozens of different species of butterflies as well as the plants they feed on.