Coleopteras

Coleopteras

Of all the animals living on the planet (excluding bacteria), beetles alone make up more than 25%, corresponding to several million species, 410,000 of which have already been catalogued. By way of comparison, mammals, of which we are a part, are represented by only around 5,500 known species.

At the National Museum of Natural History of Paris alone, with some 20 million specimens housed in 80,000 entomological boxes, beetles account for more than half of all butterfly and other insect collections. Arranged on their edges, these tens of thousands of boxes occupy almost five kilometers of shelving, which is primarily of scientific and heritage interest. With the exception of large tropical or European species, such as goliaths, “rhinoceroses” or lucans (kites), the general public and amateur collectors are far more interested in butterflies (Lepidoptera), grasshoppers (Orthoptera), dragonflies or gigantic stick insects than in beetles.

Beetles have colonized every habitat from deserts to freshwater lakes.

Yet the order of beetles is the most diverse of the insect class. According to the most pessimistic estimates, there are over a million different species – some scientists say two million – most of which will have disappeared, due to deforestation or eradication by pesticides, before they’ve even been discovered.

From tiny ladybugs (thousands of species are even smaller) to giant Goliaths, which can measure 12 to 13 centimeters and weigh a hundred grams, making them the heaviest flying insects, they can be found in all major habitats, with the exception of the polar regions and marine environments.

Some are detritivores, decomposing plant debris, while others feed on carrion or excrement (coprophagy), such as the famous “dung beetles”, which roll perfect spheres of dung or other mammalian excrement, which they later feed on or lay their eggs in. Such was the perfection of these balls that the Egyptians believed that the sun could only rise thanks to an immense beetle that pushed the star like a dung ball. Religious beliefs also made these insects a symbol of immortality and resurrection: eating the manure in which the beetle laid its eggs and fed its larvae represented a cycle of rebirth. Many beetles are phytophagous, eating leaves or tree bark, while others feed on pollen, flowers and fruit. To capture certain large specimens, specialists lure them with rotten fruit, which they feast on especially at night. There are also predators and parasites that attack other insects. The best-known example is ladybugs, which devour aphid larvae and are used as control agents in agriculture.

Many enter the food chain of various vertebrates, such as birds, reptiles, amphibians or fish, and even small mammals.

The Egyptians worshipped scarabs, a large family of beetles.

Beetles (a huge family of the Coleoptera order) have been around since ancient times, but they were revered by the Egyptians. The habits of certain beetles led the Egyptians to compare them to the sun. As we’ve already mentioned, the orange-sized ball that beetles move by rolling was compared by the Egyptians to the path of the sun across the sky. This veneration for beetles led them to make jewelry, dozens of examples of which can be admired in the showcases of the Louvre museum’s collections, as well as in virtually all Egyptology collections in museums around the world.

The sacred scarab could move from one state to another, emerging from the earth in the morning just as the sun does. The Egyptians made it an emblem of royal power, representing the sun god. The first commemorative scarab was made for a pharaoh. It was a sacred scarab with a text inscribed in hieroglyphics on its belly. Amenhotep III, ninth pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, created several models of commemorative scarabs. More than 250 are known to be dedicated to him, depicting various commemorative events of his reign, such as his marriage, his victorious battles, his lion and bull hunts, allusions to his power. If he was the one for whom the greatest number of jewel beetles have been found, before and after him and all along the course of the Nile, all pharaohs venerated these insects.

It wasn’t until many centuries and even millennia later that “scholars” rather than priests became interested in beetles and, more generally, coleoptera. Many specimens are described in Diderot and D’Alembert’s Encyclopédie or Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, published between 1751 and 1772. Less fragile than butterflies, certain collections of beetles dating back to the 18th century, including that of Lamarck (precursor of the theory of evolution, before Darwin), have survived and are now preserved at the National Museum of Natural History. Beetles appeared almost 300 million years ago, and are among the rare terrestrial organisms to resemble their fossil ancestors.

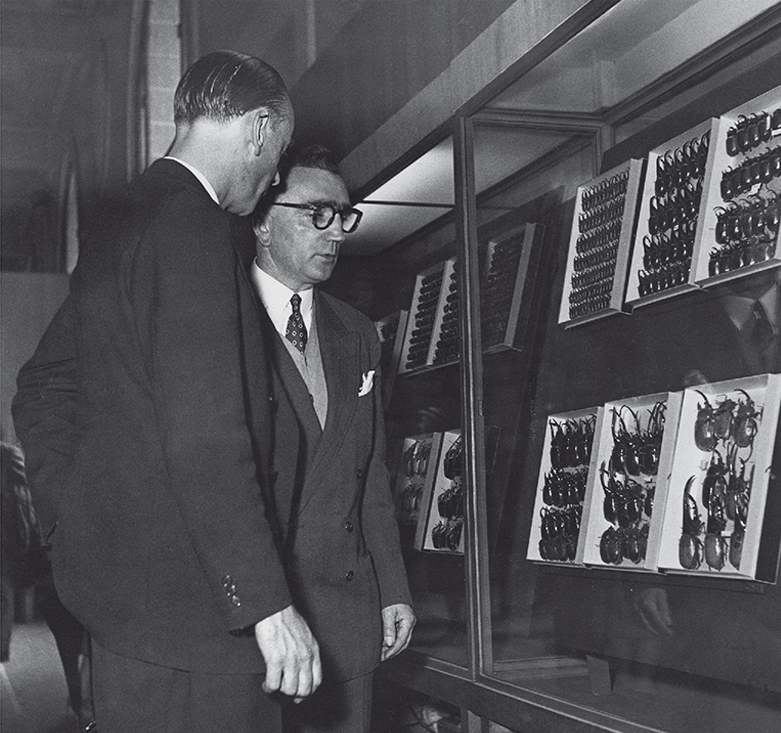

Inauguration of the Oberthür collection exhibition at the Museum on May 13th, 1953: Guy Colas (three-quarter face) and André Descarpentries in front of boxes of dynastines (beetles).

Aristotle named them after the cases (Greek koleos) that protect their wings.

Here, we should be talking about common characteristics, as the biology of the 400,000 or so species currently listed differs from suborder to suborder, from family to family and, of course, from species to species. The order Coleoptera includes insects known as “holometabolous” (undergoing complete metamorphosis), whose adult form is always preceded by an immobile pupal stage. This is also true of butterflies (order Lepidoptera), “flies” (order Diptera), “bees” and many other insects. What distinguishes beetles, and gives them their name, is that they have elytra to protect their wings. The word “beetle” comes from the Greek koleós meaning “sheath” and pterón meaning “wing”. It was Aristotle who gave them this name, a term taken up twenty centuries later by Linnaeus in his zoological classification.

These elytra, in fact the first pair of wings, are rigid and form a kind of armor, effectively protecting the insect’s thorax and especially its abdomen. Many of the insects we know, such as ladybugs, beetles, lucans (kites), chafer beetles and weevils, for example, have these elytra (upper wings transformed into protective cases) and are therefore beetles.

Among other characteristics, from the tiny ladybug to the giant Goliath or Titan, they have a rigid covering (exoskeleton) which, in addition to the elytra, protects them from shocks or predators. Their diets are extremely varied: vegetarian, carnivorous, scavengers, scavengers, coprophagous, etc., enabling them to colonize practically any environment, depending on the species. Essentially terrestrial, they live in almost all climates and have colonized all continental, terrestrial and freshwater biotopes, with the exception of Antarctica.

Europe’s largest beetle is the “kite” Lucanus.

Coming back to their elytra and rigid exoskeleton, I remember when I was salmon fishing in the Gave d’Oloron (then Basses-Pyrénées, now Pyrénées-Atlantiques) in July, and camped in the shelter of a large oak tree in a small Canadian tent, that almost every night, Lucanuscervus or kites would either fall or fly, hitting the double cotton roof with a dull thud. Early in the morning, in fact at daybreak, I often found them at the foot of my tent, numbed in the grass by the night’s dew. As I was preparing for veterinary school and had a keen interest in things natural, especially as an insect fly fisherman, I collected them and kept them in a cardboard box, along with a few oak twigs. At the end of July, when the salmon fishery closed and I returned to Paris, I often had a good twenty of them, which I would then transfer to a vivarium improvised from an old aquarium.

I exchanged a few with butterfly-collecting friends, but always kept a dozen or so, both male and female, in my vivarium. On my first “collection” and on my first night back in my room, where I had set up the vivarium on a shelf not far from my bed, I was awakened by loud cracking noises as if someone were cracking walnuts, crushing them by hand beside my pillow. I paid little further attention and went back to sleep, believing I’d been dreaming. The next night, the same sounds of dry branches breaking, made me turn on the light. The creaking was coming from the vivarium, and through the glass I saw two large male lucanid beetles whose enormous mandibles, reminiscent of deer antlers, were embracing each other, trying to crush each other’s thorax and abdomen.

If the Kite Lucanus is considered Europe’s largest beetle, it is precisely because of the male’s giant mandibles. These hypertrophied mandibles, which can reach 7 to 8 centimeters in length, are reminiscent of a deer’s antlers, hence the name “kite” for this insect when it’s a male. Only the male has such mandibles, which form a pair of large pincers. Females, on the other hand, have only short mandibles (between 1 and 2 centimeters), which act as small, pointed pincers that they use to sink into rotting wood and lay their eggs. Kite beetles use their giant pincers as fighting weapons in confrontations between males: competition between these large beetles is indeed fierce, and their jousts often give rise to impressive battles. The winner is the one who flips his opponent onto his back, enabling him to mate with the coveted female.