Cabinets of curiosities

Cabinets of curiosities

The cabinets of curiosities appeared in France and more generally in Europe during the Renaissance, and then became very numerous in the 17th and 18th centuries. They have lasted until today, and since the end of the last century, have even become “fashionable” again.

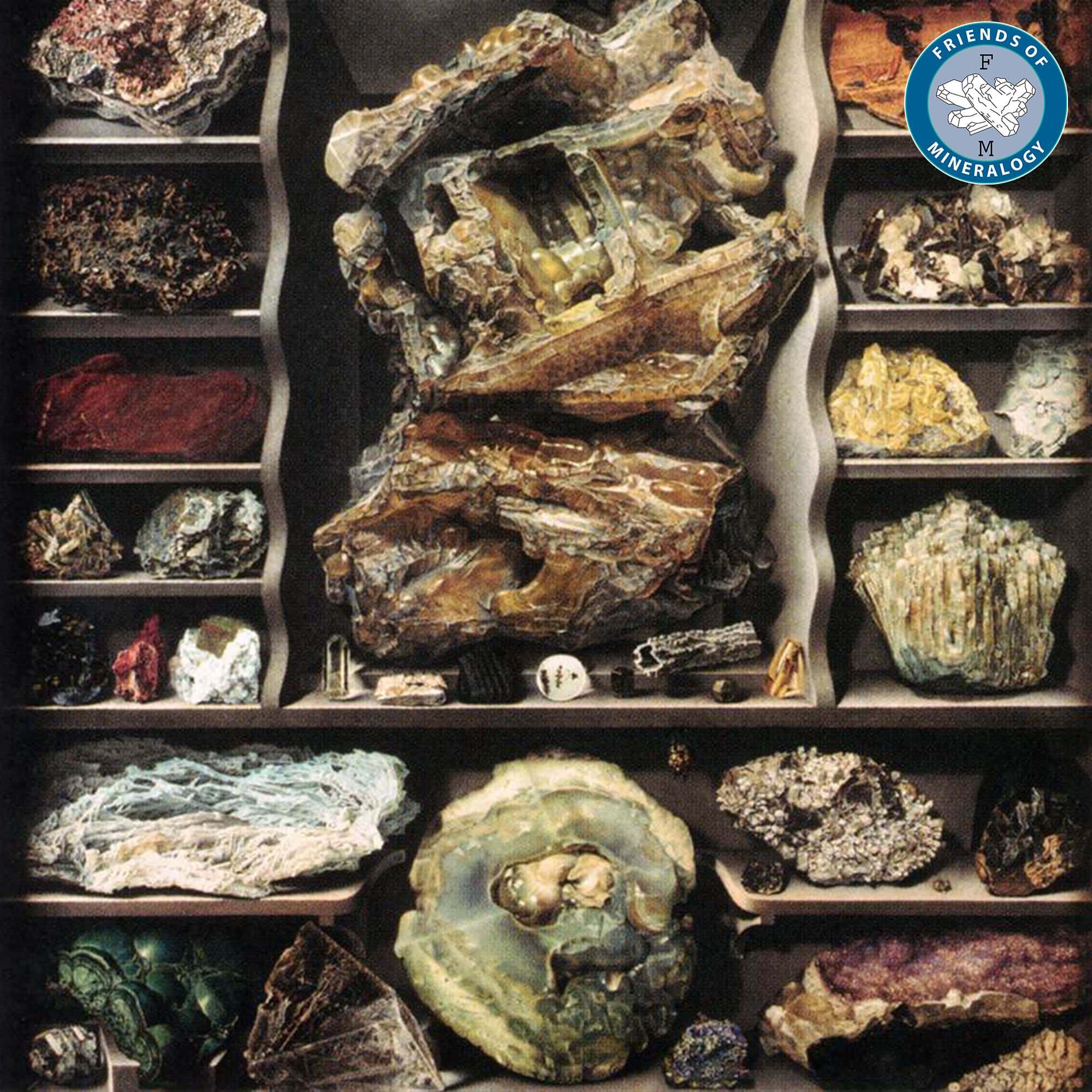

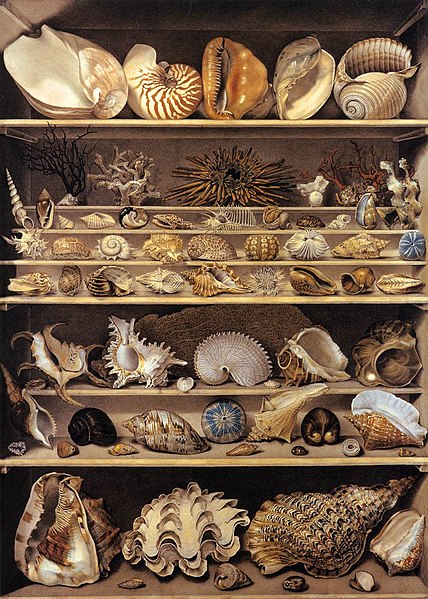

Choice of shellfish, Alexandre-Isidore Leroy De Barde

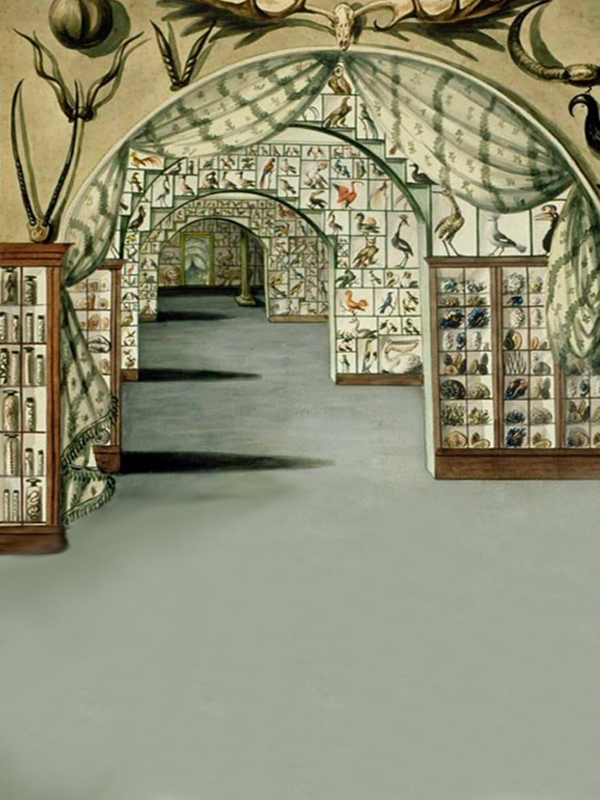

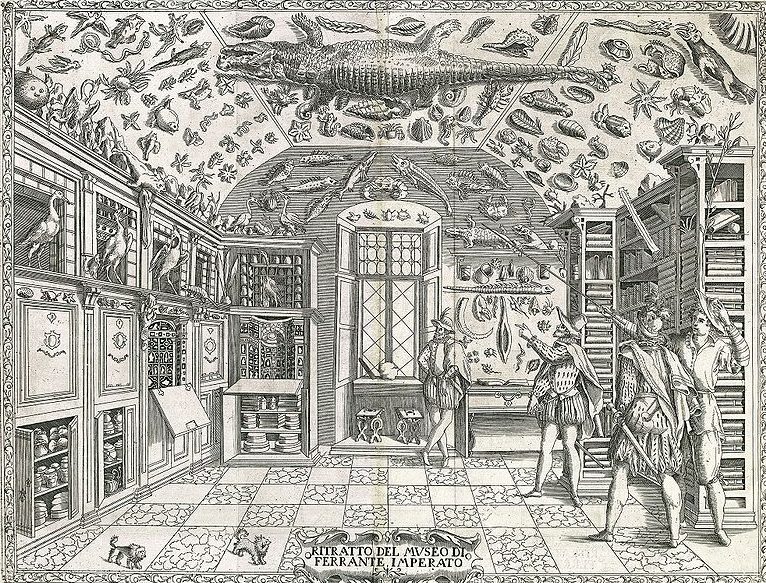

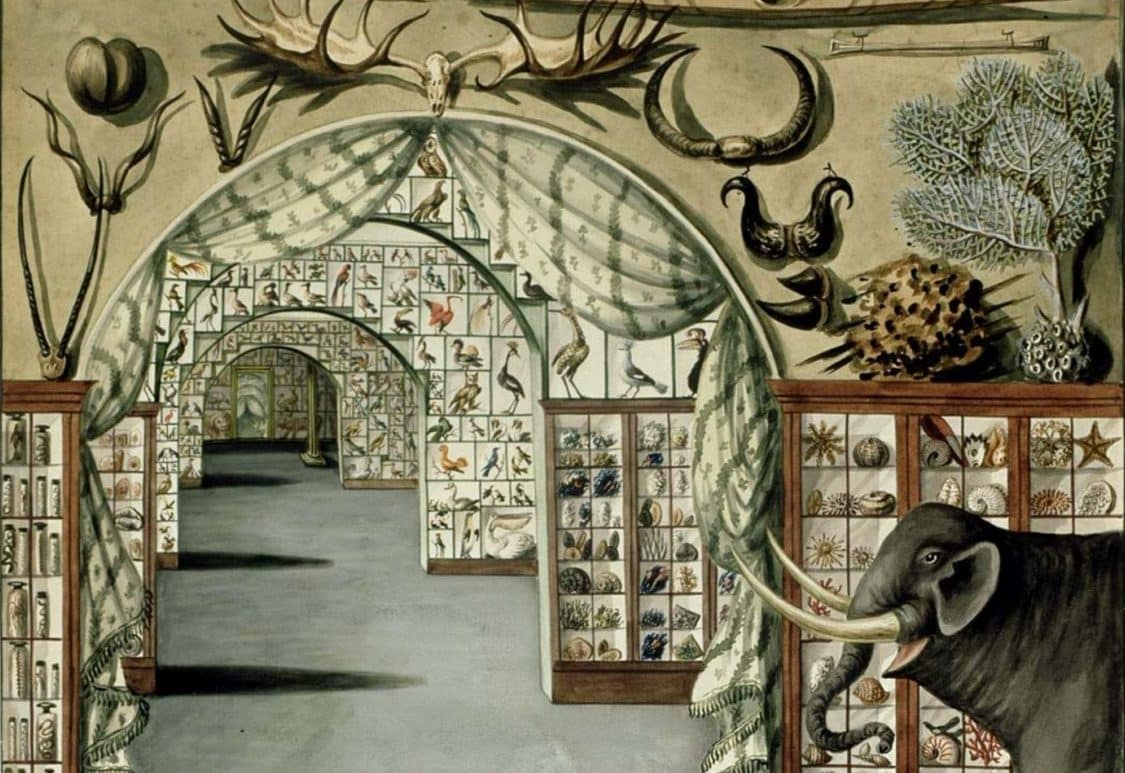

Originally, they were rooms, or sometimes furniture, where collections of rare, new or astonishing things were gathered and displayed, most often related to Natural History. If from the beginning, the mineral kingdom with notably fossils and the vegetable kingdom, with the herbariums were represented there, it is especially the animal kingdom which constituted the bottom of the collections with skeletons, carapaces, horns, teeth, shells, insects in butterfly frames and obviously stuffed animals. Their function was to better understand Nature and the World, including the distant one.

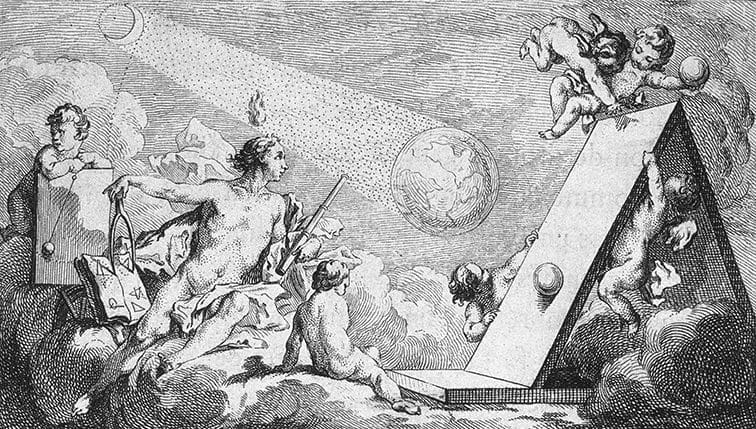

Of Natural Historia, Ferrante Imperato.

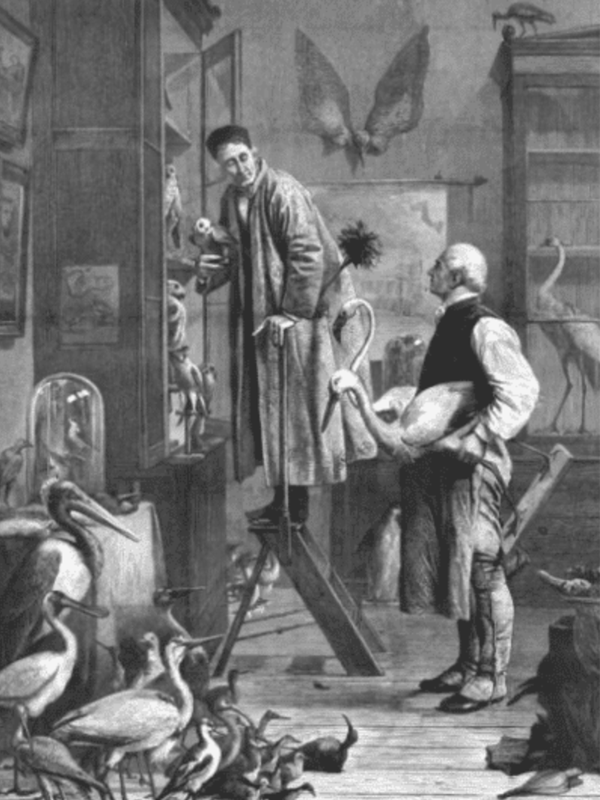

View of the Ashton Lever Museum, Sarah Stone, 1785.

Often assembled by princes, these “animal” collections were an affirmation of their omnipotence, but could be made available to “scholars” who could travel and study at home. The cabinets of curiosities thus marked an important step towards a more scientific understanding of the world. Subsequently, and especially during the 18th and 19th centuries, their collections formed the core of museums and musea open to the general public.

History and theory of the earth by Buffon, De Sève.

The Count of Buffon was the first “scientific” naturalist.

Buffon, in his famous speech on the “Theory of the Earth” in 1749, underlines the interest of gathering collections of objects, not to be astonished by their singularity but to understand and compare them. For, he warns us: “The first obstacle that arises in the study of Natural History, comes from this great multitude of objects and the variety of these objects. It is only by dint of time, care, and expense, and often by fortunate chance, that one can obtain well-preserved individuals of each species of animal, plant, or mineral, and thus form a well-ordered collection of all the works of Nature.”

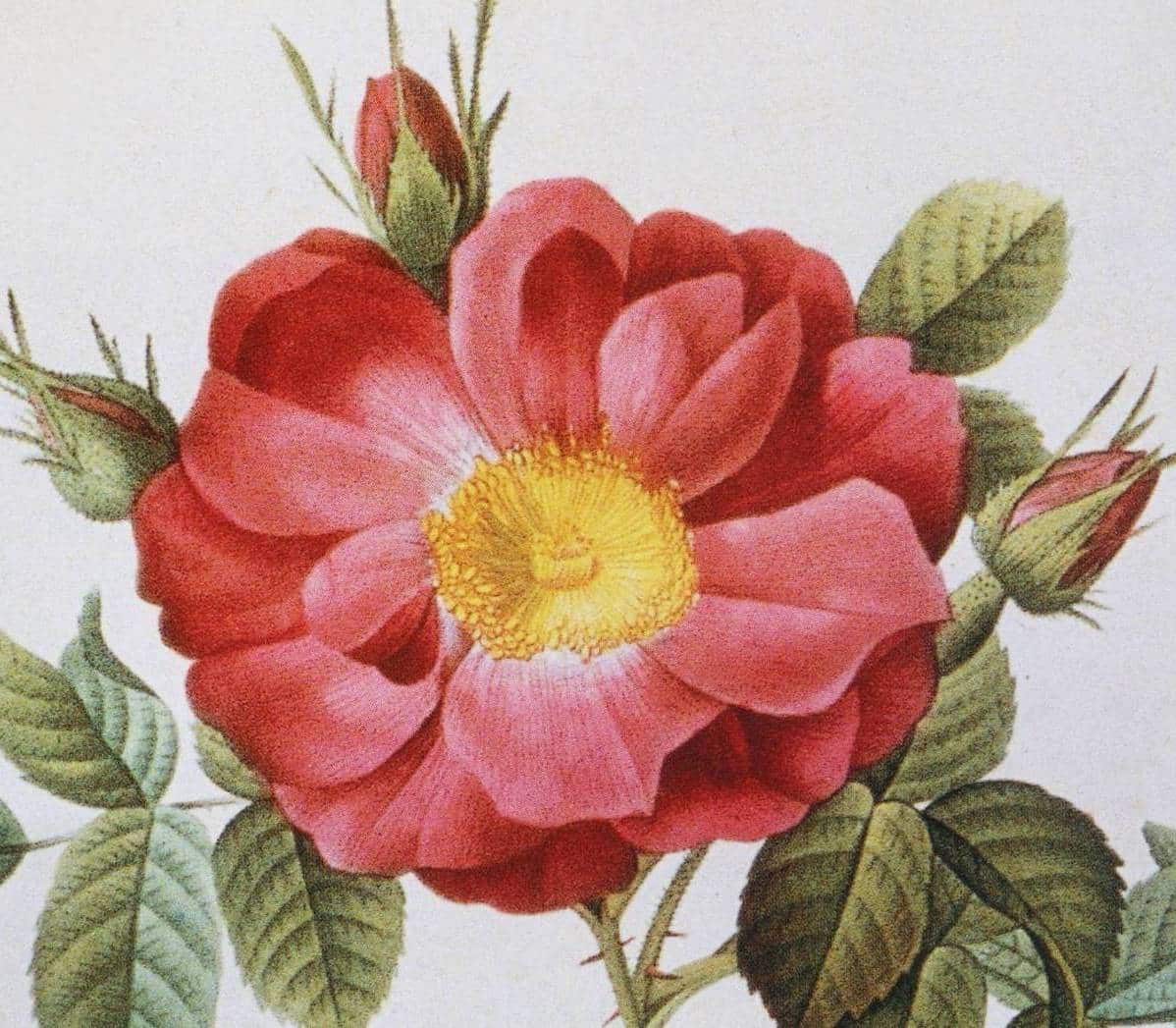

Raphael of flowers, Pierre-Joseph Redouté.

Cabinet of collections, Frans Francken II, 1625.

If Buffon, the first “scientific” naturalist, limited the cabinets of curiosities to the study of Natural History, well before him, in fact since the Renaissance, “collectors” already mixed or associated objects created or modified by man: archaeological objects, antiques, art objects, weapons, display objects (butterfly frames), and then very quickly with the development of explorations and travels of exotic animals and ethnographic objects.

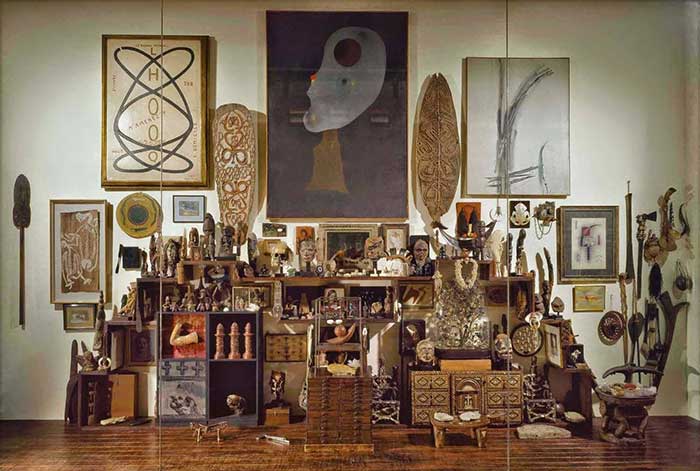

Workshop, André Breton.

From then on, the cabinet of curiosities was no longer limited to Natural History, but to an accumulative approach, as long as it was artistic, of the most diverse objects: minerals, fossils, seeds, dried plants, animals or parts of animals, carapaces, skeletons, teeth, claws, feathers, weapons, objects of art or ethnography. Its outcome could be around 1950, the “wall of curiosities of André Breton”, father of surrealism, reconstituted today in the Pompidou Center.

André Breton collected modern paintings and objects of primitive arts.

From the beginning of the 19th century, with the taste for travel and exploration and the creation of huge colonies in France and England, a real trade and even speculation on shells (easily transportable), insects (especially butterfly frames), stuffed birds and animals, as well as primitive arts objects, developed. Before becoming real sciences, conchyology (study of shells) and entomology (study of insects) benefited greatly from the fashion of the cabinets of curiosities, in which rich idlers were content to accumulate or, according to their statements, to collect mollusc shells or butterflies according to their beauty, their size, their rarity. Nevertheless, these collections, often constituted at great expense, would allow specialists to classify and study rare and distant specimens, which many museums had not yet acquired.