Morphos

Morphos

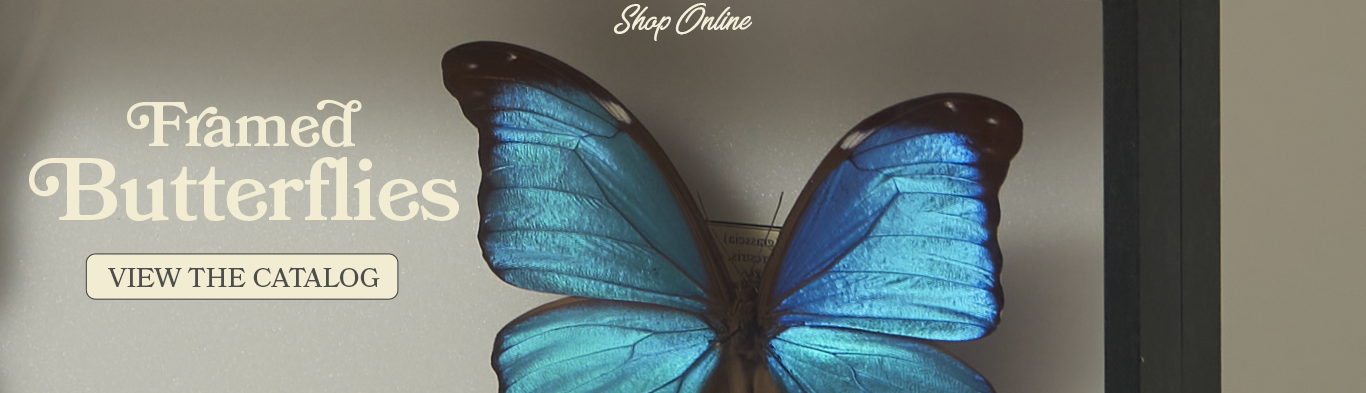

Morphos are the large “electric” blue butterflies you see framed in most curiosity cabinets. Entomologists (scientists who study insects) have classified them in the large Nymphalidae family and the Morphine subfamily, first described in 1807.

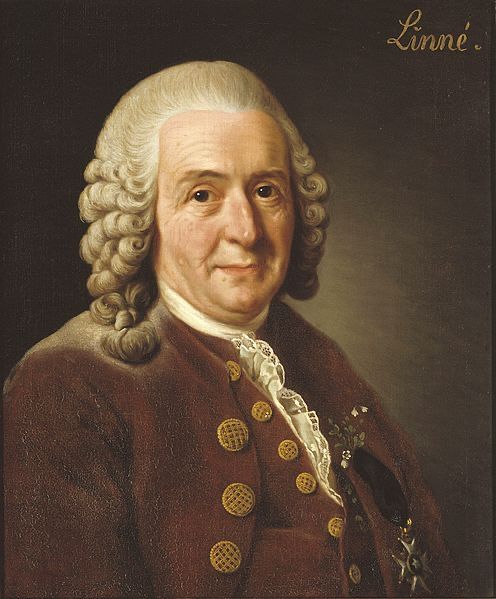

Linnaeus didn’t know them… Few animals, mammals, birds or butterflies like this one from the jungles of Amazonia, ever reached him for classification. Although he died in 1778, the brilliant Swedish naturalist who invented the binominal classification of plant and animal species, which still prevails today, had described or rather classified 3,000 species of insects during his lifetime, including over 1,000 butterflies. Their common name morpho or blue morpho can refer to several species of iridescent blue butterflies belonging to the genus Morpho.

The Swedish biologist and physician Linnaeus never classified Morphos species.

Morphos are found only in the tropical forests of Latin America.

These large butterflies live in the tropical forests of Central and South America: Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guyana and Venezuela. From the moment they were discovered, they have astonished scientists and the general public alike, with the iridescent “metallic blue” colors of their wings, or rather the tops of their wings. The underside, much more discreet, is grey or brown, depending on the species, with ocelli designed to scare off predators by imitating the eyes of birds of prey.

In the majority of species – of which there are some thirty – only the males sport this iridescent blue color. Females are generally orange-brown on top, with black borders around the edges. In a few rare species, such as Morpho menelaus, females also have metallic blue uppersides, but with a wide black band and a few white spots, making them easy to distinguish from males.

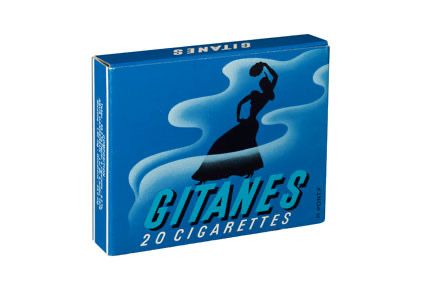

A pack of “Blue Gitanes” cigarettes to attract Morphos.

Morphos are among the largest butterflies in existence, with a wingspan of 12 to 20 centimeters, and because of their bright colors, they’re easy to spot when in flight and from quite a distance. Most of the time, males and females rest, wings folded in the dense foliage, feeding on the sap and juice of tropical fruits.

When they do fly, the males to attract the females, it’s usually high up in the open spaces of the Amazon forests. Hunters seek them out in the aerial “corridors” formed by the great rivers between their impenetrable banks. I remember fishing on the Ucayali River, which later became the Amazon, and spotting them at heights of over 40 meters.

A Brazilian friend of mine, married to a French vet from my class, told me that an infallible way of attracting them was to wave a packet of Gitanes Bleues cigarettes, a famous post-war brand, with or without filter, which no longer exists today.

This square, cardboard packet, some ten centimeters square, was metallic blue, and although I wasn’t a smoker, I had brought one with me on the huge pirogue, nearly twenty meters long and carved out of a tree trunk, on board which, with a friend, we sailed down the Ucayali for two months, from Pucalpa in Peru to the border with Brazil and Colombia, a distance of over 1,000 kilometers, not counting the meanders.

As we moved from one fishing spot to the next, scanning the tops of the tall trees on the banks, often more than half a kilometer away, I saw a morpho flying, and shimmered my pack of Gitanes in the sun. I would then ask the guide to stop our boat’s course, and sometimes the big blue butterfly, believing a competitor to be on its territory, would come down to our pirogue, where we could admire it up close.

Forty years later, I can still see them, as the sight of a large morpho in its natural habitat, the Amazon rainforest, is unforgettable. Along with the pink river dolphin, the blue morpho is certainly one of the species that captures the true atmosphere of the Amazon, wild, impenetrable and luxuriantly beautiful.

The blue color of their wings does not fade in the light.

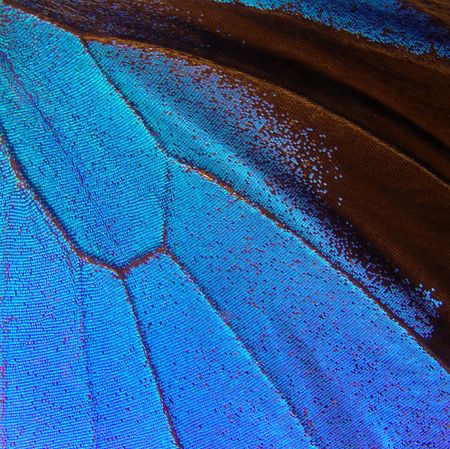

However, the luminescent blue of the morphos’ wings is only an appearance, albeit a blue one, depending on the incidence of the light rays shining on them. It’s the microstructure of their wings and the stack of tiny scales that cover them – let’s not forget that the common name for butterflies is Lepidoptera, which comes from the Greek and means wings with scales – that gives them this blue iridescence when they are illuminated, by sunlight or artificial light. Iridescence is the property of certain surfaces that appear to change color according to the angle of illumination.

The feathers of a few rare exotic birds, such as the Cotingas (small passerines of the Amazon rainforest), much sought after by Victorian salmon fly tyers, exhibit the same light diffraction phenomenon.

Whereas most of the feathers of the most colorful birds fade and become dull if exposed to light for too long, the iridescent blue plumage of Cotingas, like the wings of Morphos, are not afraid of light, and can therefore be displayed without fear in a curio cabinet window.