Coleoptera collecting

Coleoptera collecting

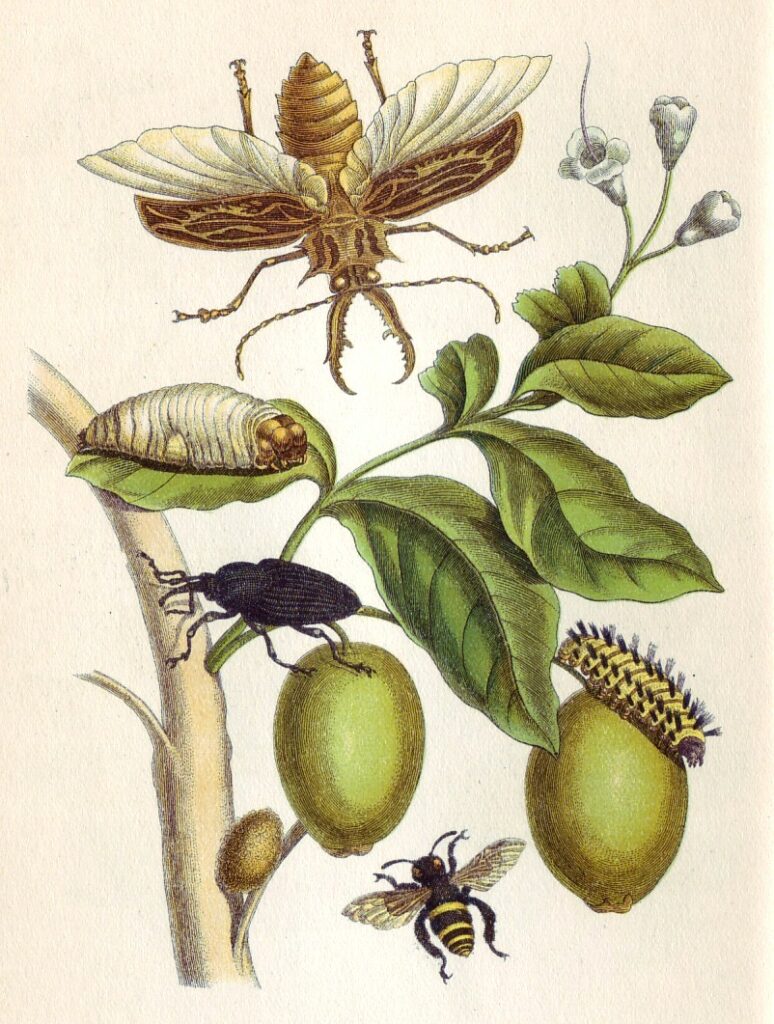

With the exception of kite beetles, because of the “terrifying” appearance of their gigantic mandibles, and a few other “big” European beetles such as longhorn beetles, still known as “capricorns”, very few of our beetles are of interest to amateur collectors. The same is not true of exotic beetles, most of them tropical, whose size, shape and coloring prompt curiosity cabinet enthusiasts to display them in glass entomological boxes, where these species never fail to catch the eye and intrigue visitors.

Some beetles (Coleoptera) can lift almost a thousand times their own weight.

The Titan, also aptly named, both vernacularly and scientifically (Titanus giganteus), is a candidate for the title of world’s largest insect, with a size exceeding 16 centimeters. Of course, it’s also a beetle, belonging like the capricorn beetles to the large family Cerambycidae. It is found in the rainforests of South America: Colombia, Peru, Brazil, Ecuador, Guyana.

Most of the insects in this family, which includes the “capricornids” or “longicornids”, are highly sought-after by collectors, due to their generally large size and especially their very long antennae, which are a great curiosity in glass entomological boxes.

Capricorn beetles owe their name to their long antennae (horns), which are larger than their bodies, particularly in males. This characteristic makes them easily recognizable by amateur collectors. These disproportionately large antennae are said to act as a pendulum during flight. Their larvae feed on wood, which is often rotten, and these insects can be found in virtually all the world’s forests, both tropical and temperate.

In Thailand's Chiang Mai province, locals organize rhinoceros beetle jousts, with betting.

Another large family of beetles of interest to the collection, due to their large size and rhinoceros-like cephalic and thoracic “horns”, are the Dynastes. These beetles can grow up to 15 centimeters long, including their horns. Only the males have these horns, which can be single, depending on the species, or present in threes or fours, for others. Males use these characteristic horns in mating fights. The best known is the Dynastes hercules, the strongest of the “rhinoceros beetles”. This species, found in Central America and the French West Indies, can lift up to 850 times their own weight.

By way of comparison, if a human being of average height and weight had the same strength, he or she would be able to lift an object weighing 65 tons. In Thailand’s Chiang Mai province, locals organize rhinoceros beetle jousts, with betting. Official matches take place under the gaze of thousands of enthusiasts during a festival broadcast on national television. Belligerent only during the mating season, the males feed on nectar, plant sap and fruit.

Adapted to all environments, some beetles are almost exclusively aquatic.

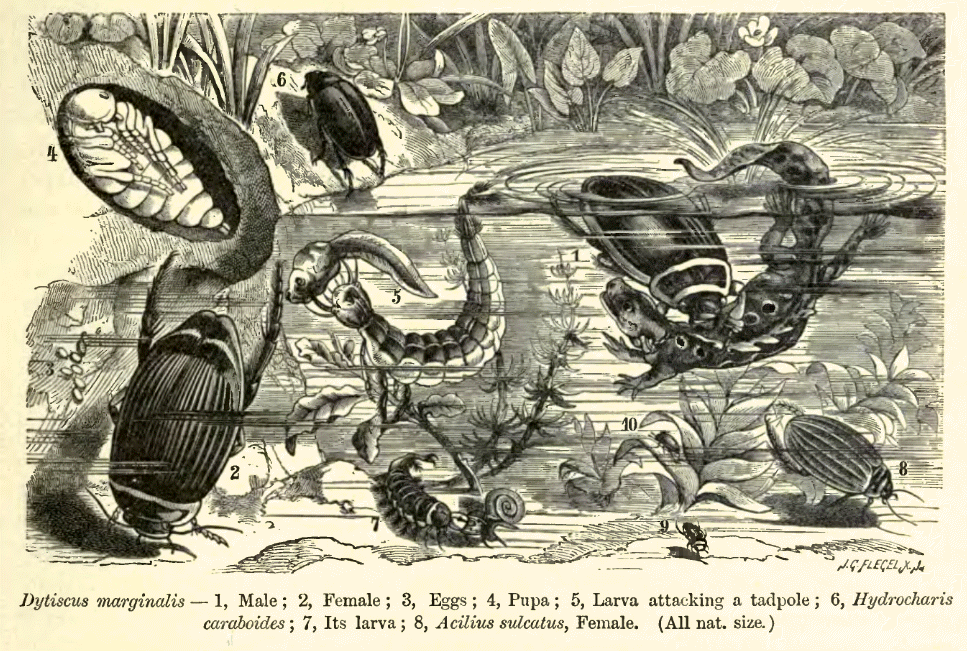

While most beetles are terrestrial insects – and we include those that live in trees – many species spend most, if not all, of their lives in water. This is particularly true of dytics, which children who fish for tadpoles and newts in ponds occasionally catch in the mesh of their landing nets. The Dytiscidae is a family of aquatic beetles with almost 4,000 known species worldwide.

They can be found on every continent, in every region except arid deserts. Most of them are carnivorous freshwater predators, not hesitating to attack larger prey such as small frogs or fish. But even more voracious than the adults are their larvae, sometimes called “freshwater tigers”, which hunt by lying in wait, locating their prey by vibration and olfactogustation.

They have a venom containing digestive enzymes which they inject into their prey with their mandibles, whose imposing size also immobilizes their victims. The prey’s internal organs then liquefy under the action of the enzymes. The dytic larva can then suck out the contents, leaving only an empty shell.

The common name, dytique, for these insects derives from the ancient Greek dytikos, meaning “that likes to dive”, or rather “that likes to swim”. Adult dytics resemble bulging cockroaches. For better hydrodynamics, their head is recessed into the thorax, and their body forms an almost perfect oval. Like all insects, they have three pairs of legs, the hindmost of which are flattened like oars, enabling them to swim very efficiently. Dytics have no gills, but breathe through tracheae like other insects. They regularly rise to the surface to replenish their air reserves beneath their elytra.

Although they spend more than 99% of their lives in the water of ponds, most dykes are able to fly and move to other ponds when their habitat dries out. The most common species in Europe is the bordered dytic, named after the yellow edging on its carapace (thorax and elytra). As they can reach a size of 3 to 4 centimeters, the almost perfect oval shape of their body and their original color (dark green tending to black edged with golden yellow) always make them popular insects, especially given their aquatic life, in an entomological box.

Finally, many species of ground beetles, not especially large ones, are highly sought-after by collectors for their shimmering green colors in every conceivable shade. Personally, I prefer lucanes, not black ones like our “kites”, but all those that combine browns from the lightest to the darkest, and which remind me, by their shapes and colors, of high-class English shoes with well-shined leather.