Big game fishing

Big game fishing

Often referred to as “Big Game Fishing”, this sport of fishing is essentially aimed at large marine fish such as tuna, marlin, swordfish and, to a lesser extent, sharks. This type of fishing is best known to the general public through the accounts of Hemingway, Zane Grey and, in our country, Pierre Clostermann, the ace of the Second World War.

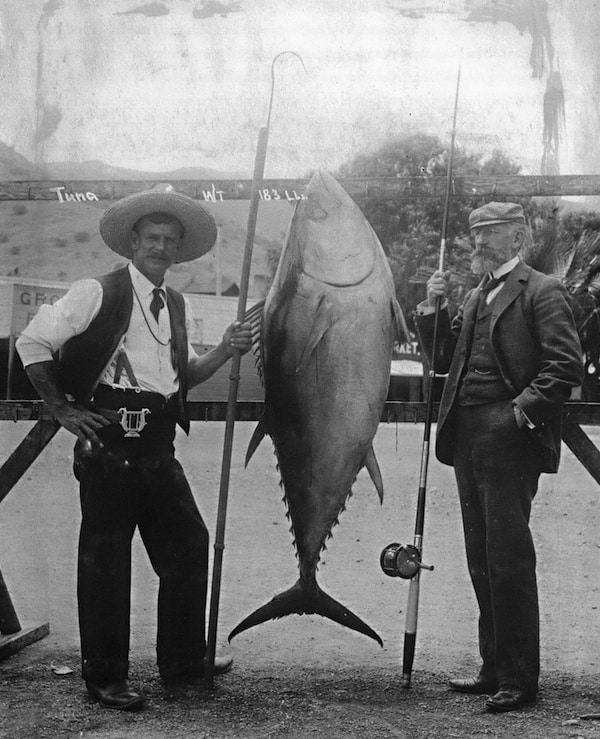

The first "big game" in history: a 183-pound bluefin tuna by Charles F. Holder in 1898.

It was in California on June 1st, 1898, that the first “big one” in history was caught with a rod and reel. It was a 183 pound bluefin tuna, and the happy fisherman Charles F. Holder, along with a few other enthusiasts of this new sport, founded the Catalina Tuna Club the following year, named after the island off which this catch was made.

And what Frederic Halford in England, a few years earlier, had brought to trout fishing by transforming it into a gentleman’s pastime, the very well-to-do “sportsmen” of the Catalina club did for big game fishing, by also enacting very strict rules that all members had to commit themselves to respect.

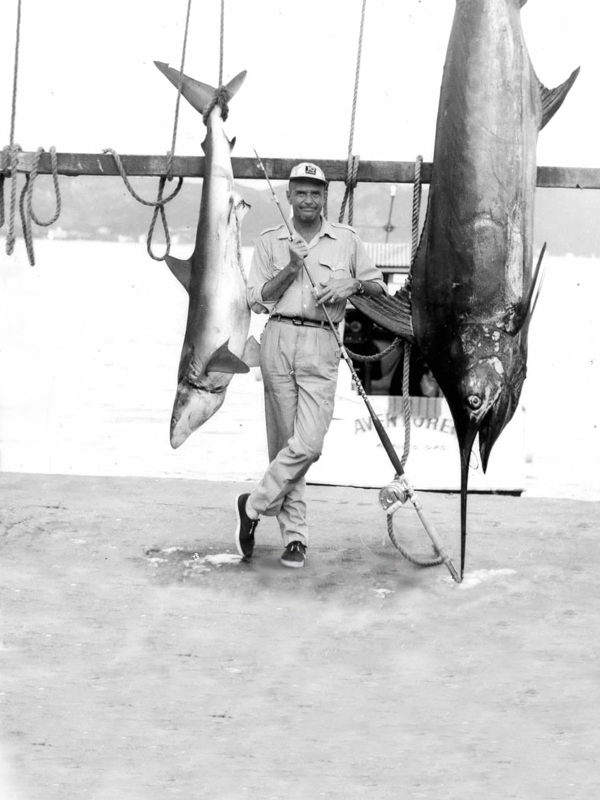

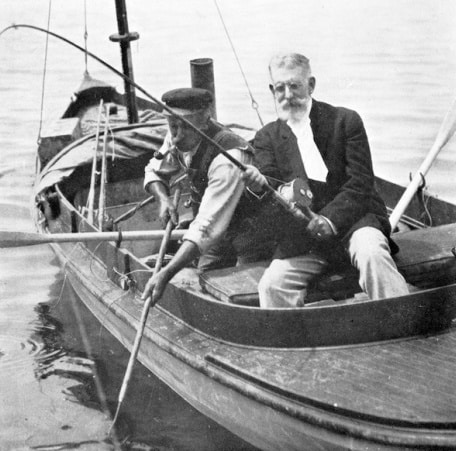

Charles F. Holder preparing his equipment.

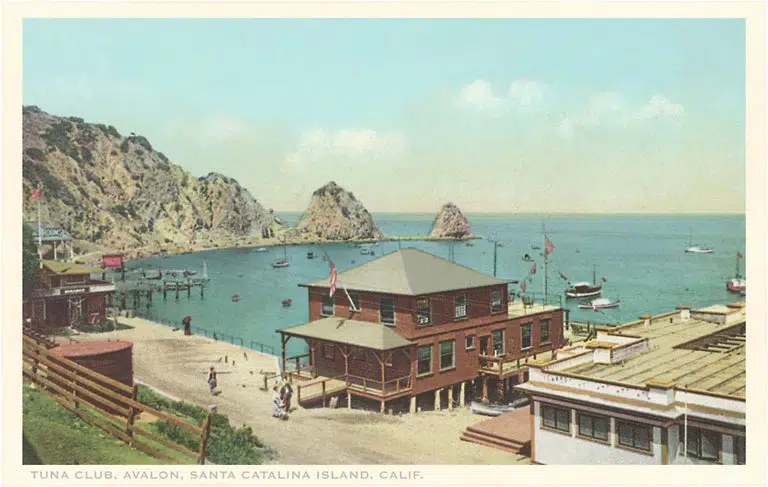

The famous Catalina Club on the island of the same name, opposite Los Angeles.

These “marvelous madmen”

fishing on their funny boats.

It was not so much the catch that counted, but the way it was caught. To become a member of the Catalina, one had to have caught a tuna weighing more than 100 pounds according to the rules, i.e. with a light rod and a line of no more than 24 strands.

The lines of the time were made of braided linen that had to be rinsed with fresh water, unrolled and carefully dried after each fishing trip. A line of 24 strands had a resistance of about 50 pounds and these “marvelous fishing fools” on their funny boats, attacked from the beginning the two species of fish still considered today as the most combative: the bluefin tuna and the swordfish.

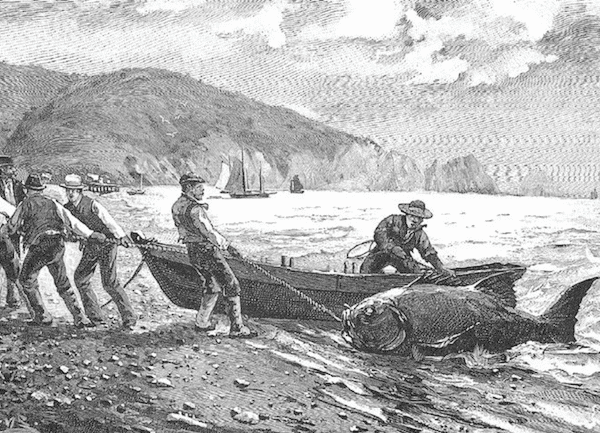

Charles F. Holder brings a nice tuna to the gaff.

Still off Catalina, a Tuna Club member approaches a fish from the gaff.

Avalon Santa Catalina Island.

The real handicap was the braking of the fish which, once hooked, took off with all its fins, because the reels of the time were only large spools, attached to a crank and containing 300 to 400 meters of line. And this crank, turning in the opposite direction at the speed that one can imagine when the tuna fled, the fisherman then had for only resource to press strongly a piece of leather on the spool with his right hand, with the aim of slowing down enough the rotation of the spool so that his left hand could seize the crank.

The number of broken phalanxes and even wrists in this game was uncountable and in Los Angeles or San Francisco, the distinguished members of the Catalina Club were said to be recognized by their left hand in a cast every other month!

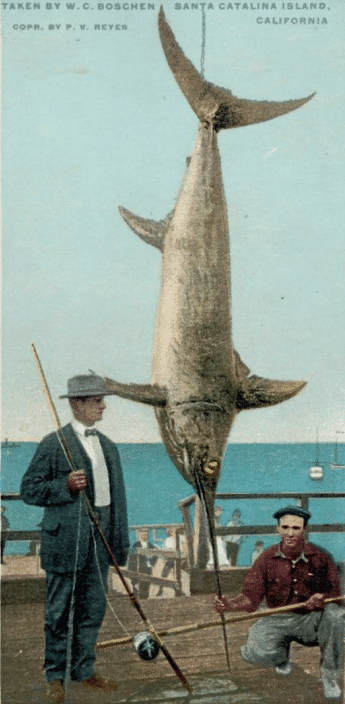

William Boschen with a real swordfish (Xiphias gladius) of 358 pounds, caught in 1917.

These pioneers were not discouraged, however, and very soon one of them, William Boschen, no doubt annoyed by the forced inactivity caused by these plastered fingers, invented in 1911 the first reel with a built-in brake, more or less as we know it today, at least in principle.

And to prove that his machine worked, he caught the first swordfish in the history of the “Big Game”, a splendid 358 pound specimen. He was the first to become a legend. Zane Grey, Lerner, Ernest Hemingway, Farrington and, for France, Pierre Clostermann and Guy Real del Sarte were to follow.

In Cuba, Ernest Hemingway with a nice blue Marlin of the Gulf-Stream.

In the United States, women are not left out. Sara "Chisie" Farrington with a women's record bluefin tuna.

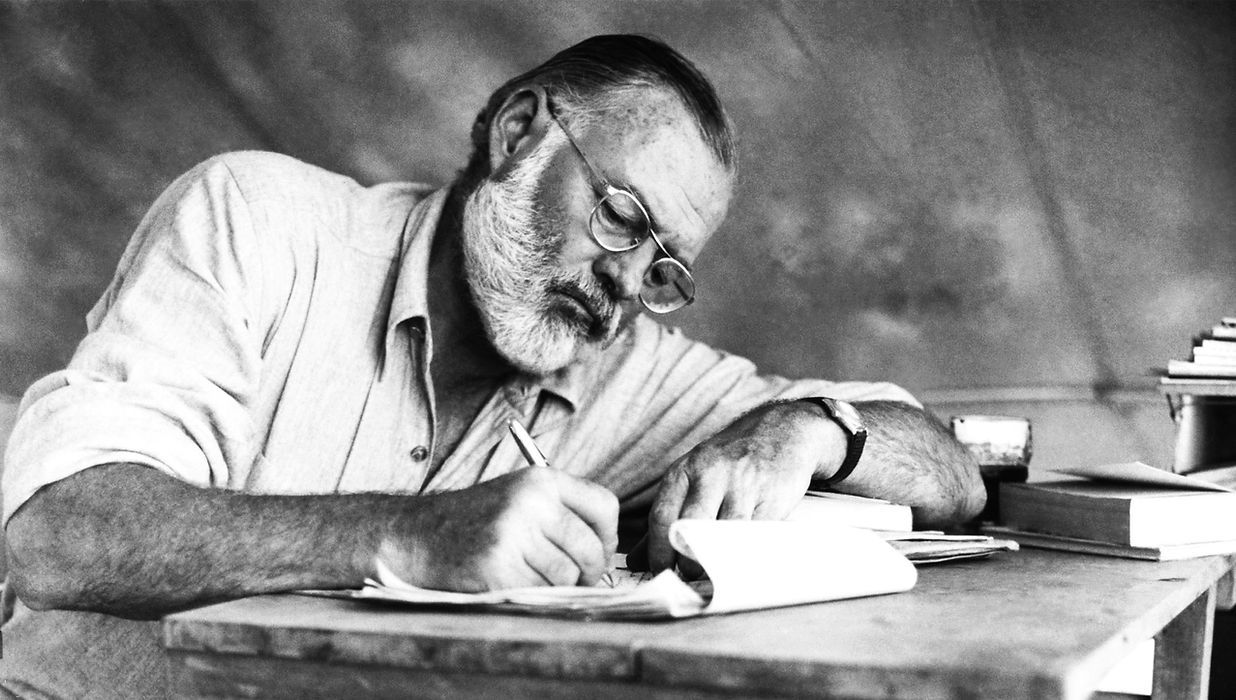

Hemingway laid down the rules and created the International Game Fishing Association.

In Key-West or Cuba, Hemingway wrote early in the morning, and fished every afternoon.

THE IGFA. (International Game Fishing Association) was created in 1939 by M. Lerner and E. Hemingway.

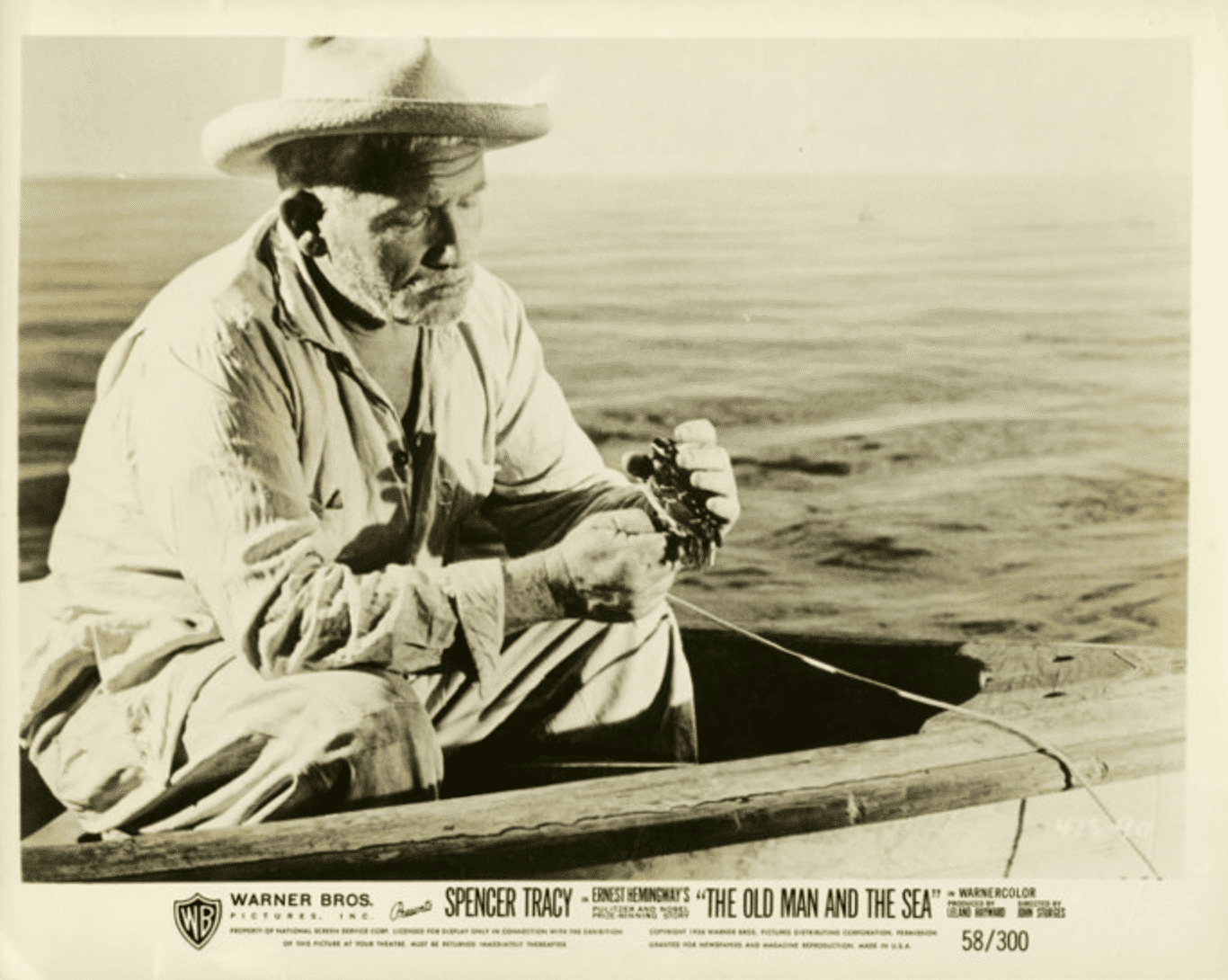

We have all read and even reread the adventures of Hemingway’s old man’s fight against, not a swordfish – as translated by Jean Dutourd for Gallimard – but a giant blue marlin from the Gulf-Stream. Although fictionalized, the story actually took place in the 1930s, off the coast of Cuba. An old fisherman from Cojimar, a small port east of Havana, was found half-mad, drifting alone in his boat in the middle of the Gulf Stream with the carcass of a gigantic marlin tied along the hull. The fish had towed the boat for more than 60 hours before giving up the fight and being devoured by sharks.

In the movie "The Old Man and the Sea", Spencer Tracy, plays Santiago, the old Cuban fisherman.

The poster of the film, shows the "old man" fighting the sharks that devour his big fish.

Spencer Tracy, in the role of Santiago, the old Cuban fisherman.

Of course, the boats of the Cuban fishermen of the time were not much bigger than those that can be rented today to go around the lake of the Great Cascade in the Bois de Boulogne, but all the same, to pull a boat against the current in the Gulf Stream and over several tens of miles, one understands that this can be really sport fishing, even and especially, I would say, if the line is held by hand.

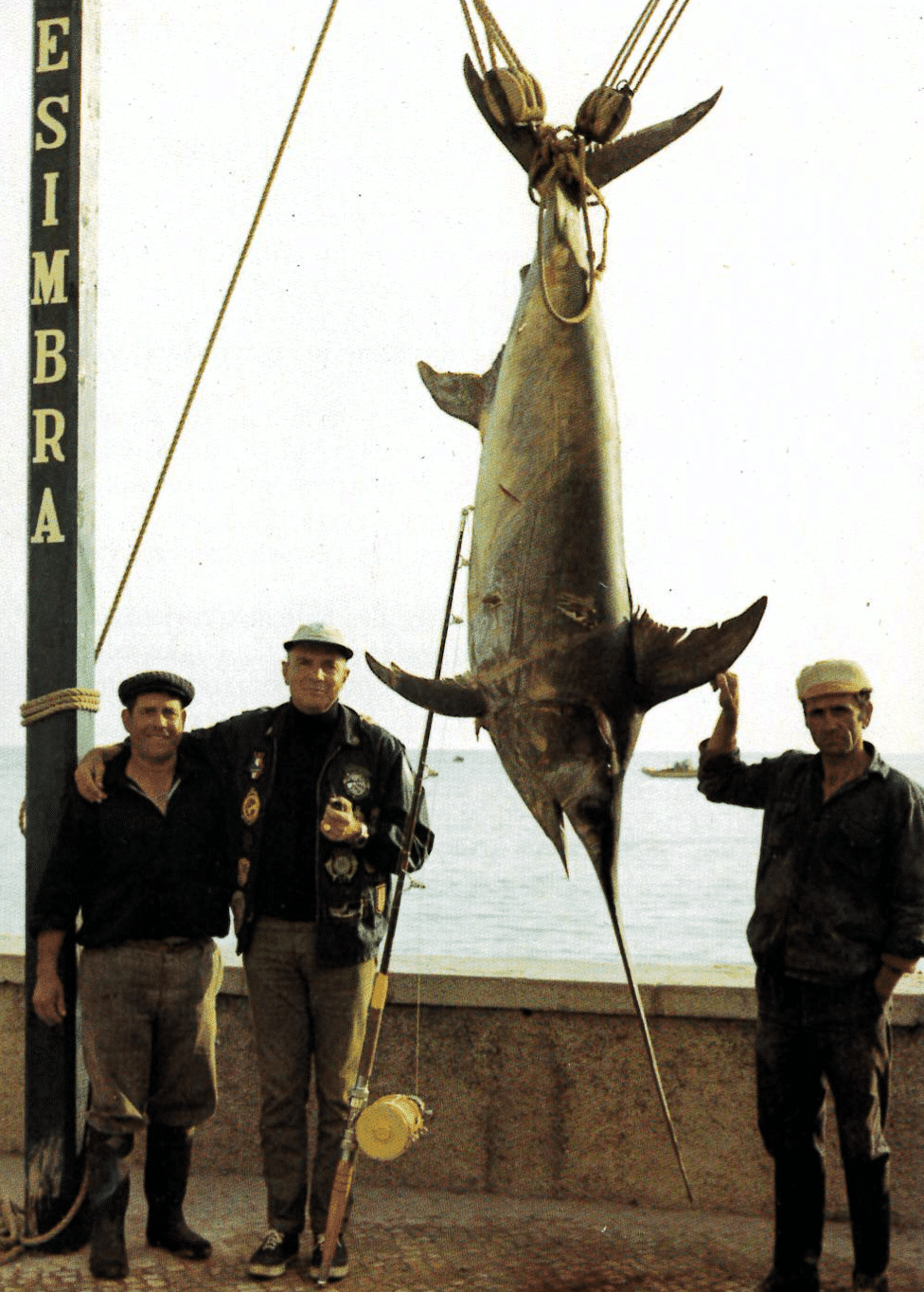

To remain in the chapter of walnut shells, we must speak here of fishing with a rod and reel this time, of real swordfish (Xiphias gladius) off Sesimbra (Portugal), as practiced for many years by Pierre Clostermann in the company of a few other European pioneers of big game fishing.

(From “Des poissons si grands” Flammarion 1969). This is what great sport fishing was, just a few decades ago.

Pierre Clostermann with a beautiful swordfish caught in Sesimbra (Portugal).

Founder of the BGFCF (Big Game Fishing Club France) and successful author of great sport fishing around the world.

For the purists, the modern and ultra-sophisticated equipment makes the capture too easy.

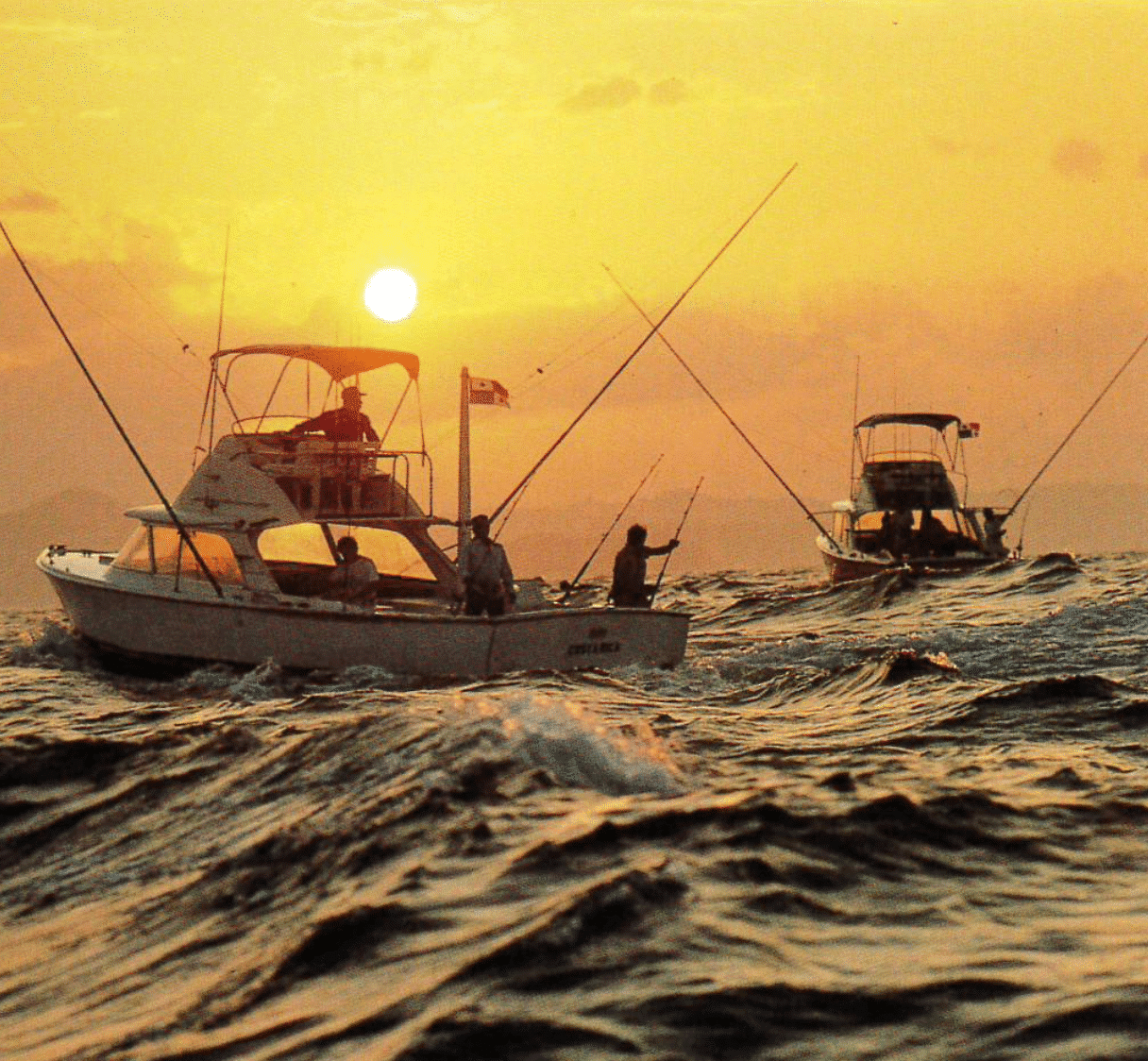

In Florida, very efficient "cabin cruisers" are especially dedicated to "all-big game" fishing.

Compared to these fishing feats, the catching of billfishes of more than a thousand pounds as it is practiced today, in Cairns (Australia), Madeira or the Azores, from boats capable of backing up to more than ten knots on the fish, seems to us to be a little pale.

Fortunately, fish that are caught very quickly and that have not always had time to realize what is happening to them, are almost always released. But is this still a sporting feat, as Hemingway and Lerner meant it when they created the IGFA ?

Catching a marlin or a tuna weighing more than a thousand pounds in less than ten minutes seems to us to be more of a technical feat, to be attributed mainly to the skipper and the crew who know how to take advantage of all the possibilities of highly sophisticated boats.

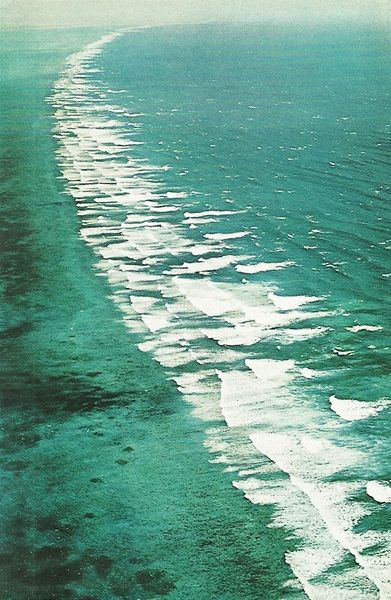

By backing up at full speed on the fish, the skipper will force it to fight on the surface on a tight brake and a short line. In the impossibility of sounding, the marlin or the tuna will not be able to find cooler and more oxygen-rich water layers at depth. In the warm surface waters, they will suffocate more quickly.

In addition, it is always to the fisherman’s advantage to keep the fish on the surface because by maneuvering around the fish, it will be easy to counteract all its directions of escape. When a large marine fish has sounded (sometimes at more than one hundred, two hundred or three hundred meters), besides the fact that the water pressure weighs with all the height of the liquid column on the resistance of the line (let’s remember Pascal’s barrel experiment), there is no way to orientate efficiently, at the vertical of the fish, the traction in one direction or the other.

In South Africa, big game fishing can be done by "surf-casting" from the beach.

All the art of the great skippers of giant tuna or marlin consists, when the configuration of the fishing grounds lends itself to it, in keeping the fish hooked on the shallows, in preventing them from returning to the drop-off (where they would not fail to sound) and in forcing them to make increasingly abbreviated sprints during which they literally suffocate. This is the technique initially used off Bimini to catch giant bluefins (bluefin tuna) as well as off the Australian Great Barrier Reef.